Throughout the Qur'an, various signs are presented so that the reader may be invited to reflect on and, through introspection, understand that there is a singular creator/sustainer, that idol worship is futile, and that the Qur'an is from God not the product of the prophet (ﷺ). These signs are of various degrees and of different appeals for different audiences. It appeals to natural signs (Surah 3:190), prophesying the future (Surah 41:53), linguistic inimitability (Surah 17:88), profundity of its parables/lessons(14:24-25), but an understudied and under-cited proof that the Qur'an also appeals to; is its knowledge of the contents of biblical material given the environment which it was formed. In the late antique context of Hijaz, the Qur'an emerged from an environment which lacked biblical literacy and literacy in general, yet the Qur'an interacts with and polemically engages in complex, nuanced discussion in Jewish and Christian topics from dozens of different literary sources. This indicates that the Qur'an was not the product of a context from which the prophet(ﷺ) emerged from, but rather something that came from beyond the Hijazi environment.

In these series of upcoming articles, I will explore an oft-cited but often overlooked argument of the Qur'an for its divine origin. When recounting events of biblical figures such as Mary, Moses, Noah, Joseph (peace and blessings of Allah be upon them all), the Qur'an frequently cites a repeated refrain of the Prophet (ﷺ) and his immediate audience knowing about these events as proof that this Qur'an should be taken as something not coming from the Prophet (ﷺ) but rather originating from God (cf. surah 11:49, 12:3, 28:46). The Qur'an adjusts pivotal details of stories in the bible, engaging in dialogue within Judeo-Christian materials which were only known among its experts, and shows subtle linguisitic knowledge of Hebrew and Syriac vocabulary which could only be known among experts of the people of the books. These key interactions were passed over by the immediate 7th century Hijazi audience, only to be picked up by later erudite scholars from the people of the book from later generations who were well-versed in the scripture or recent Quranic studies experts who have extensively studied Hebrew and Syriac. The sheer quantity and quality of these interactions and its lack of reception by its immediate audience shows that the Prophet(ﷺ) was not fabricating the Qur'an from his surroundings. Given that the hypothesis of the Qur'an emerging from another surrounding which was not Mecca or Madinah, but was highly biblically literate is unfeasible, this book emerging from 7th century Mecca/Medinah could only best be explained as having emerged supernaturally.

Meccan/Medinan Milieu

Before exploring the question of intertextuality in the Qur'an, it is important to first consider the socio-cultural and historical context of 7th-century western Arabia---particularly the state of literacy and the extent to which a biblical environment may have existed. Traditional Islamic sources, such as the sīrah literature, consistently portray Mecca as having extremely limited literacy before the advent of Islam. Historians such as al-Balādhurī report that only a small number of individuals from the Quraysh tribe---seventeen, could read and write.¹ This shows a broader picture of a society where oral tradition played a central role, with poetry functioning as the primary medium for preserving memory, expressing identity, and maintaining tribal prestige. In such a context, oral transmission---rather than written documentation---was the predominant form of communication and knowledge sharing.

This literary scarcity in Islamic historical records is further corroborated by archaeological and epigraphic data. As Christian Julien Robin (2001) notes, there is a noticeable absence of inscriptions in the western Arabian Peninsula from approximately 355 to 644 CE.² While a few inscriptions from the pre-Islamic Ḥijāz have been uncovered in recent years, they remain rare and are far fewer than those found in other parts of the Arabian Peninsula. Regions such as South Arabia (home to the Sabaean, Minaean, and Himyarite civilizations) and the Syro-Arabian desert have higher inscriptions documenting various aspects of political, religious, and social life. This contrast highlights the Ḥijāz's marginal position in terms of scribal culture during Late Antiquity.

Another piece of evidence pointing to the limited role of writing in the pre-Islamic Ḥijāz is the absence of any confirmed translation of the Bible into Arabic prior to the 8th century. In surrounding regions---Abyssinia, Syria, and Egypt---biblical texts were already available in Geʿez, Syriac, and Coptic by the 6th century. In contrast, no Arabic translations or substantial fragments of the Bible have been identified from the pre-Islamic period, either through literary sources or archaeological discoveries.³

Because of this lack of literacy in Hijaz, some scholars such as Gabriel Said Reynolds have instead opted to advocate for the presence of an oral culture in the Ḥijāz that transmitted Jewish and Christian material. He cites the Qur'an's indirect engagement with biblical material---its allusions, paraphrasing, and repurposing of biblical phrases--- rather than using direct verbatim quotations as evidence of such a cultural presence.⁴ However, this argument can be challenged on two fronts.

First, aside from the general lack of inscriptions, there is also little concrete evidence for the existence of established Christian communities in the Ḥijāz, or for Jewish communities in Mecca and its immediate vicinity. While Jewish presence is well-documented in parts of the northern and central Ḥijāz---such as Medina, Khaybar, and Taymāʾ---the archaeological and historical record remains notably silent regarding any such presence in Mecca.

Some might argue that the well-attested Jewish communities in Medina, could have served as a conduit for the diffusion of Jewish traditions into the Qur'an, but this assumption rests on a highly problematic leap: namely, that the mere presence of a community necessarily implies significant cultural or theological exchange with outsiders. But this is not a given. To use an analogy, the presence of a large and vibrant Jewish community in New York City does not mean that the average New Yorker is familiar with the contents of the Talmud.

Robert Hoyland comments on the absence of any jewish inscriptions found in Yathrib, Tayma, Khaybar despite quite a large number of epigraphical surveys being conducted at all three sites, saying that most Jewish inscriptions are concentrated at al-'Ula and Mada'in Salih. He explains this as indicating that most Jews in the Hijaz region were well integrated into the Arabian culture, having but a rudimentary familiarity with Judaism and its rituals and being "minimally inducted" in high Jewish culture given its limited contact with the wider Jewish world. ⁵

Crucially, the Qur'an itself—our earliest and most direct source— indicates that the Jews of Medina’s knowledge of scripture and doctrinal matters was confined to a learned elite, with there being Jews among them who were "unlettered" or unfamiliar with the contents of the scripture (cf. Qur'an 2:78).

If this was the case among the Jewish population itself of having groups of people who have no knowledge of scripture, it is even more unlikely that the surrounding pagan Arabs would have had access to or absorbed detailed theological material from the elite Jewish class. The Qur'an repeatedly refers to the early Medinan audience---particularly the polytheistic converts---as people "who did not know the Book" (cf. Qur'an 4:113; 2:151), categorizing them alongside the Meccan polytheists as religiously uninformed. This evidence indicates that pre-Islamic Medina, like Mecca, did not exhibit widespread familiarity with Jewish religious texts, and undermines the notion that Jewish tradition had permeated the broader cultural fabric of the region in any meaningful way prior to the Prophet's mission, which is consistent with the broader findings of Robin of a lack of any Arabic New or Old Testament translation.

As for Christian presence, historian Harry Munt has pointed out that although scholars have attempted to trace Christian communities in the Ḥijāz region, the evidence offered is often weak.⁶ No late antique sources on episcopal geography mention bishops in the central Ḥijāz, and a Christian writer in the 11th century explicitly states that Christianity did not spread into the Hijaz, largely because missionary activity was focused on the courts of Kinda and Yemen.⁷ This lack of Christian and Jewish presence in Mecca raises serious questions about the plausibility of a widespread "oral Bible" culture there. For such a milieu to exist, a robust and visible presence of Jewish and Christian communities would have been necessary.

Second, one of the examples Reynolds offers to support his view---that the Qur'an reuses biblical language for different purposes---may not actually demonstrate such a repurposing. In the case of the Qur'anic reference to a camel passing through the eye of a needle, a closer examination in this article will reveal that the surrounding context preserves much of the same thematic content as its biblical counterpart, suggesting not a reinterpretation but rather a resonance with the original message.

For this to be done, a rough breakdown of what intertextuality means and different types of intertextuality will be explained and examined in the Qur'an.

Intertextuality

To understand the term "Intertextuality", one helpful way is to break down the word into its constituent parts.

Inter + textual + ity

The prefix inter is a latin prefix which means "in between", the term textual refers to anything pertaining to literary works, and the suffix -ity refers to the state. ⁸Therefore, the term "intertextuality" can be roughly broken down as "the state (i.e the relationship) between texts"

It is important to note, however, that in the context of Qur'anic studies, the investigation of intertextuality aims to identify instances of deliberate literary engagement between the Qur'an and biblical or extra-biblical texts. This involves examining whether the Qur'an is consciously alluding to, reworking, or responding to pre-existing textual traditions in a way that reflects intentional interaction.

This differs from merely observing that the Qur'an and other literature share similar motifs, themes, or narrative elements. Those similarities could arise from a shared heritage that exists in the broader cultural context. Intertextuality, in the stricter sense, requires evidence of textual awareness or dialogue to be considered an interaction. In other words, the task is to distinguish whether the parallel in the Qur'an indicates intentional interaction (such as allusion, adaptation, or transformation of a known text), rather than the similarity arising from a loose diffusion or transmission of widely circulating ideas, symbols, or motifs in the ancient near eastern milieu.

Criteria of interaction between two texts?

While there is no clear cut and dry method for determining if there is intentional interaction going on between two texts, the following are some methodologies which are used for determining if the Qur'an is intentionally interacting with other texts.

Linguistic Interactions

The Qur'anic text is notable for its consistent use of core vocabulary, so when there is the sudden introduction of a word that is rarely used and seems to have origin in another language, it should give us reasons to believe that the term is especially significant. When such a term happens to align with a word used in Biblical or extra-Biblical literature, this may indicate that the Qur'an is deliberately signaling a literary relationship to a biblical or extrabiblical text.One way to determine if this is occurring is to see if the term is a Hapaxalegomen (a term for words that are only used once in a text) or to see if there are words in a particular Qur'anic narrative which are mentioned rarely, or only mentioned in recounting narratives of Jews and Christians. This is typically an indication that the Qur'an is intending to use those rare words not common in its vocabulary to allude to a dialogue with a motif or portion of a story found in other literary sources of Jews/Christians.

To give one example of this, in Surah 39:63, and Surah 42:12 the Qur'an states that the keys of heaven and earth belong to Allah(سبحانه و تعالى) alone.

Figure 1.0: Surah 39:63 (M.A.S Abdel Haleem)

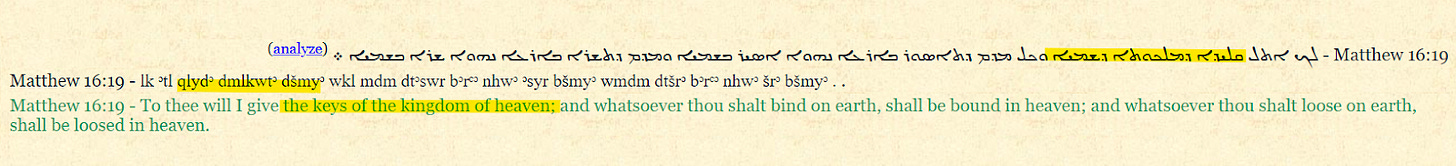

In Matthew 16:19 Jesus(عليه السلام) states that the keys of the kingdom of heaven have been given to Peter, implicitly implying the church has been given authority by God over who is admitted to Paradise.

Figure 2.0: Matthew 16:19 Peshitta (Dr. John W. Etheridge)

The Qur'an however states that the keys of heavens and the earth belong to Allah(سبحانه و تعالى) alone, affirming sole authority to Allah to admit or reject people from paradise, making it more exclusive. One reason to believe this is an intentional interaction with Matthew 16:19 rather than a common motif circulating is that rather than using the more common Arabic word for keys which is "مَفَاتِحَهُۥ" used throughout the Qur'an (cf. 6:59, 24:61, 28:76); the Qur'an uses the less common term for key "مَقَالِيدُ (maqaleedu)".¹¹ Furthermore this term for keys "مَقَالِيدُ (maqaleedu)" is only used twice, both in conjunction with the term "heaven and earth. This indicates an intentional allusion to the Syriac of Matthew 16:19 which uses the term "ܩܠܝܕܐ (qleeda)" when saying the term "ܩܠܝܕܐ ܕܡܠܟܘܬܐ ܕܫܡܝܐ (qlyda d-malkutha d-shmaya "key of the kingdom of heaven")¹². Given that both contexts seem to use the term "keys of heaven" when referring to admittance into paradise, this interaction should be best understood as Qur'an engaging with Matthew 16:19 and correcting the notion that any human have the authority of admitting people into paradise and instead affirming Allah(سبحانه و تعالى) having sole authority to admit people into paradise.

In addition to the case of uncommon words being used by the Qur'an to suggest intentional allusion; another way the Qur'an could allude to a bible passage is by using words which although common in the Arabic language, occur in specific combination in the Qur'anic passages which parallels the combination of words used in the biblical passage. An example to explain this is the Qur'anic interaction of Surah 3:96-97¹³ with Psalm 84:6-7¹⁴:

Figure 2.0: Surah 3:96-97 (Saheeh International)

Figure 2.1: Peshitta text of Psalm 84 Aramaiac CAL

As one can see, each Arabic word underlined in green has a corresponding word in the Syriac Peshitta passages to finally culminating with the term ܕܒܟܬܐ (d-bekhtā) and بِبَكَّةَ (bi-Bakkah) which while not cognates are similar enough to be used for wordplay by the Quranic author engaging with this Psalm.¹⁵ As one can also see in addition to linguistic connections, one also finds parallels in content in both surah 3:96-97, which indicates that the different methods of interaction do not have to be seen as mutually exclusive but more likely than not will have instances of overlapping of different intertextual tools.

Thematic/Content Parallels

Aside from linguistic interactions, there can also be instances where a biblical motif is recounted in differing ways, but there is one account in Qur'an which mirrors the content more closely of a specific bible passage. The parallels with a specific biblical passage and not other bible passages on the same content makes it difficult to conclude that this is the product of a coincidence and instead points to deliberate interaction.

One way to this can be determined is to examine whether the sequence of thematic points mentioned in the Bible aligns with the Qur'an sequencing. Although the Qur'an may alter the order for thematic or rhetorical purposes, if the overall narrative flow for the particular biblical passage and Qur'an is identified as being stronger than other bible passages, this indicates a deliberate interaction.

An example of this can be found in the Quranic ayah of Surah 22:47-48 which references the motif of a thousand years being like a day to God, a passage which can be found in both 2nd Peter 3:4, 8-9 and Psalm 90:4. Yet in spite of this motif being present in Psalm 90:4; thematically there are more points of connection with 2nd Peter 3:4,8-9 than Psalm 90:4. (For the purposes of highlighting the interactions, the text from the Qur'an and Peshitta will be colored and presented with numbers, to more easily show the connections).

Figure 3.0: Surah 22:47-48 (Translation M.A.S Abdul Haleem)

Figure 3.1: 2nd Peter 3:4 & 2nd Peter 3:8-9

Figure 3.3: Surah 22:47-48 & 2nd Peter 3:4,8-9 numbering/colour coding comparison

As seen above, aside from the cognates which consist of words common to both languages, all other points of connection are thematic in nature. Both texts include a reference to people who mock the coming of the punishment of God by asking for it to be hastened (Surah 22:47, (1)), and people who are in doubt regarding its arrival, (2nd Peter 3:4 (1)) (red), both texts have the motif of a thousand years of humans being like a singular day to God (2nd Peter 3:8, (2))(orange), both talk about God not faltering in his promise (2nd Peter 3:9, (3))(green), and both talk about delay of the punishment (2nd Peter 3:9, (4))(blue). The parallel passage in Psalm 90:4 simply states that in comparison to human lifespans who are mortal, a thousand years passes like a day in his sight. There is no talk about punishment by deniers or mockers, or delay or God not differing or slowing in his promise. As we can see despite no significant cognate or linguistic interaction the thematic parallels are still sufficient to indicate intentional engagement with this specific biblical passage by the author of the Qur'an.

While determining the list of correspondences for a literary interaction cannot be scientifically or mathematically determined, a useful parallel can be drawn from statistics. In statistics a minimum of three data points is generally required to begin detecting a trend. Similarly, in the study of Qur'anic and Biblical parallels, if there are three or more points of correspondence---whether in content, sequence, or theme---this can serve as an indicator that the Qur'an is likely engaging with a specific biblical tradition rather than merely coincidentally mentioning themes or content which parallel a bible passage.

Conscious Corrective Lens

Another key indicator used in evaluating whether the Qur'an's intertextual interaction is intentional, is seeing if the Qur'an consciously corrects biblical material in a way that polemically counters the message of the bible. Given that such correctives or modifications details are absent in all versions of the Bible accounts but appear in the Qur'an exclusively, the corrective can be seen as intentional theological amending for its own purposes, which indicates it is aware of the version circulating and is purposely interacting with this account to amend it.

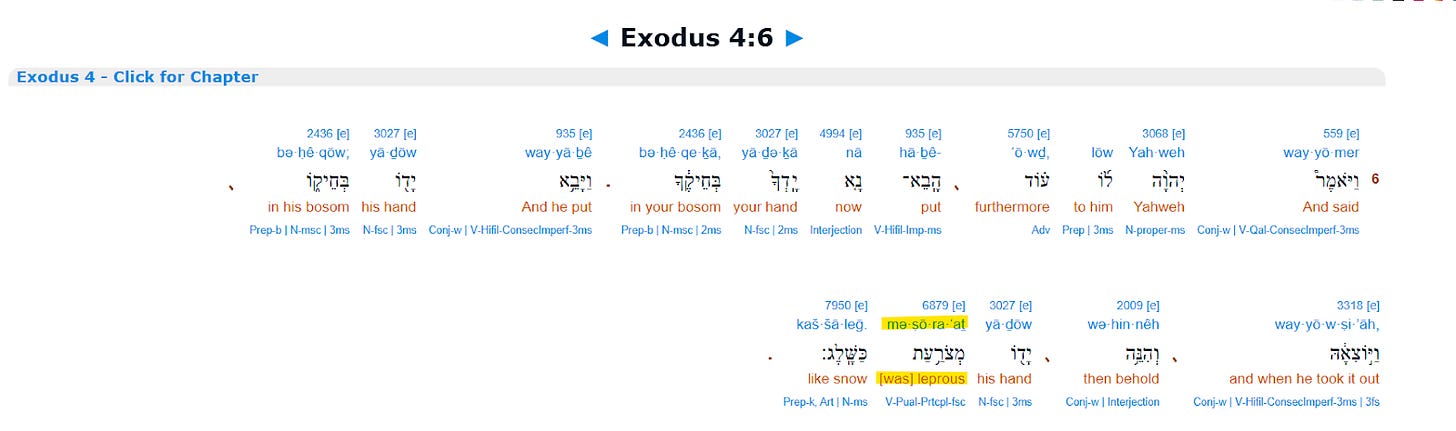

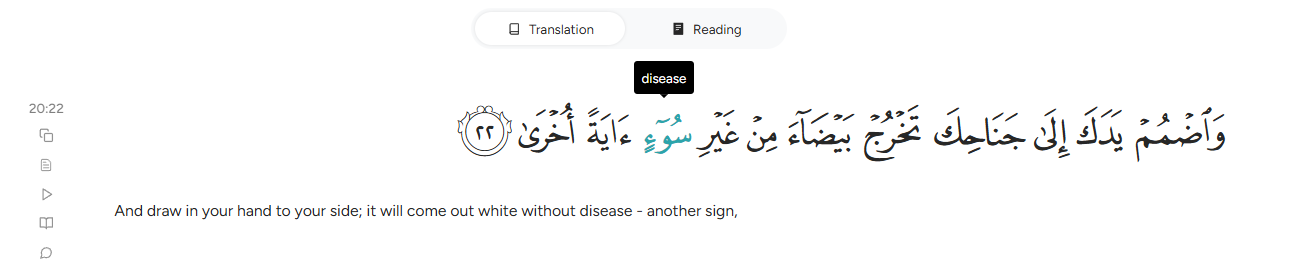

An example of this type of interaction can be found regarding the account of Musa(عليه السلام) meeting with Allah(سبحانه و تعالى) in the burning bush where he is told to put his hand within his chest and when he takes it out it emerges white with no disease.

The bible says in Exodus 4:6 ¹⁸that Moses' hand came out leprous like snow (i.e as white as snow), while the Qur'an in Surah 20:22 ¹⁹says that Musa’s (عليه السلام) hand came out white without disease.

Figure 4.0 Interlinear Hebrew Text of Exodus 4:6 from Biblehub

Figure 4.1: Surah 20:22

Why would the Qur'an have to say "without disease", when nothing in the Quranic narrative indicates his hand would be diseased? The obvious need to add a qualifier when not necessary is best explained as polemically and intentionally interacting with what the passage in Exodus 4 says and therefore best seen as an intentional intertextual interaction.

Other examples of these can be found to be scattered throughout the Qur'an and demonstrate that the notion that the Qur'an is merely inheriting circulating stories or oral tradition is faulty as they cannot best account for these amends that suggest conscious correction and awareness of why these corrections are necessary.

Revisiting Eye of the Needle

Gabriel Said Reynolds points out that the Qur'an uses the image of a camel passing through the eye of a needle---an image also found in the Synoptic Gospels---but applies it in a different way. In the synoptic Gospels (Mark 10:25, for example), Jesus says it's easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God. The Qur'an, however, uses the same metaphor in Surah 7:40 to describe how those who deny God's signs will not enter Paradise until a camel passes through an eye of the needle.²⁰ According to Reynolds, this shows how the Qur'an borrows biblical language but reshapes it to a different effect, indicating its not referencing the actual biblical material but just using or reworking a biblical turn of phrase "in the air" so to speak. ²¹

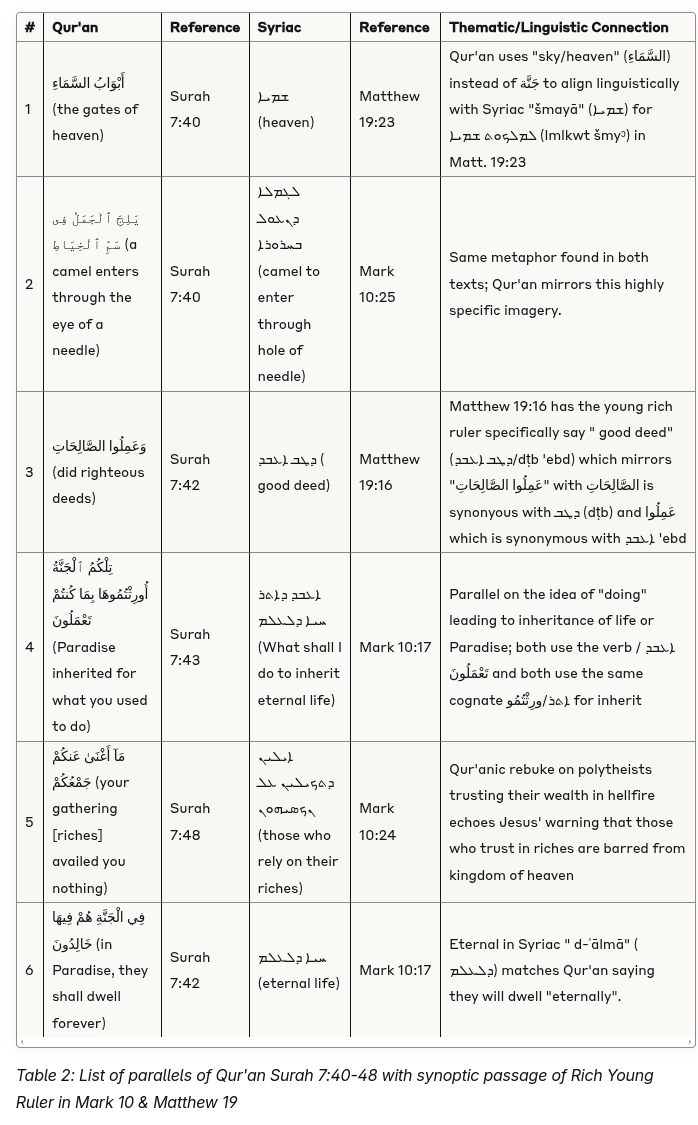

But when we look more closely at the surrounding verses in the Qur'an, we can see that it's actually still engaging with the same themes found in the Gospel story of the rich young ruler (Mark 10:17--31).

For instance, eight verses later, in Surah 7:48, the people of Paradise call out to those in Hell: "Your great numbers and pride didn't help you." According to classical commentators like Ibn Kathīr, this means that their wealth and status which they relied on didn't protect them from God's punishment. ²²This lines up with Jesus' warning in that chapter that those who trust in their riches are barred from the kingdom of heaven (Mark 10:24 Syriac), and also aligns with the broader theme of Jesus(عليه السلام) saying that riches will prevent people from entering the kingdom of God.

Likewise Surah 7:42, says those who believe and do good will live in Paradise "eternally" matching the description of the young rich ruler in Mark 10:17 in Paradise, who asks how to inherit "eternal life". This is further compounded by the next verse where the Qur'an even uses the word inherit (ورِثْتُمُو) to describe how the righteous will receive Paradise---another link to the Gospel wording of "inheriting" (ܐܬܪ) eternal life using the same cognate.

These thematic parallels and linguistic parallels indicate that rather than the Qur'an not referencing the synoptic gospel parallel, it is instead closely engaging in dialogue with the motifs found in the gospels.

So, even though the Qur'an changes the specific type of person who faces the impossible task of getting through the eye of a needle, it still seems to be engaging with the same story. It keeps the larger message about what really blocks people from salvation---whether it's wealth or arrogance or disbelief. In this way, the Qur'an isn't just borrowing biblical turns of phrases; it's interacting with the entire synoptic dialogue.

Table 2: List of parallels of Qur'an Surah 7:40-48 with synoptic passage of Rich Young Ruler in Mark 10 & Matthew 19

Conclusion

Figure 4.0 Triple Venn Diagram mentioning different types of intertextual interactions

The following categories are some of the most pertinent when it comes to the topic of intertextual interaction. Obviously, as one can tell, and as shown above there, will inevitably be overlap between these three different interactions, such as linguistic interactions with content interactions, or content interactions including corrective interactions, but this break down gives a rough guideline on what to look for when looking at Quranic interaction with the Bible and how to demonstrate intentionality in these interactions. The objective of this series is to go through examples of each of these different types of interactions, develop a table compiling all the interactions of the Qur'an based on their different types, and to then based on the large quantity of interactions show that the Qur'an is not the product of 7th century Hijazi environment. The next articles will focus on case study examples and finding the total number of literary interactions retrievable at the moment, and addressing various proposed hypotheses used to explain the large amount of literary interactions within the Quranic corpus.

Footnotes

¹ Baladhuri,1988, Kitab Futuh Al-Buldan Volume 1 Page 453 دخل الإسلام وفي قريش سبعة عشر رجلاً كلهم يكتب - "Islam emerged while there were seventeen men in Quraysh who could write..."

² Robin, 2001, Les inscriptions de l'arabie antique et les études arabes pg. 557

³ Ibid. pg. 559

⁴ Reynolds, 2018, The Qur'an and the Bible: Text and Commentary pg. 3

⁵ Hoyland, Robert G. 2008 The Jews of Hijaz and their inscriptions. Academia.edu. Pg 114

⁶ Munt,2015, "No Two Religions": Non-muslims in the Early Islamic Hijaz pg. 252

⁷ Ibid. pg. 253

⁸ Etymonline https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=intertextuality

⁹ M.A.S Abdul Haleem,2004, The Qur'an: A new translation, quran.com ,Surah 22:47-48

¹⁰ DUKHRANA BIBLICAL RESEARCH, Peshitta New Testament, Matthew Chapter 16 verse 19

¹¹ El-Badawi, Emraan (2013). The Qur'an and the Aramaic Gospel traditions. Routledge. Pg 148

¹² DUKHRANA BIBLICAL RESEARCH, Peshitta New Testament, Matthew Chapter 16 verse 19

¹³ quran.com/3/96-97

¹⁴ CAL PROJECT, Peshitta Old Testament Psalm 84 https://cal.huc.edu/get_a_chapter.php?file=62027&sub=084&cset=U

¹⁵ Neal Robinson,2004, Sūrat Āl ʿImrān and Those with the Greatest Claim to Abraham, pg. 14-15

¹⁶ M.A.S Abdul Haleem,2004, The Qur'an: A new translation, quran.com ,Surah 22:47-48

¹⁷ Dr. John W. Etheridge's, DUKHRANA BIBLICAL RESEARCH, Peshitta New Testament, 2nd Peter 3:4, 3:8-9

¹⁸ https://biblehub.com/interlinear/exodus/4-6.htm

¹⁹ https://quran.com/20/22

²⁰ Reynolds, The Qur'an and the Bible: Text and Commentary pg. 259

²¹ Reynolds, The Qur'an and the Bible: Text and Commentary pg. 3

²² Ibn Kathīr,Tafsir al-Qur'an al-Azim, Vol. 3 Pg. 422 " لا ينفعكم كثرتكم ولا جموعكم من عذاب الله" (your great numbers and wealth did not save you from Allah's torment)